In the News

News

Dec 06, 2020

A Design of Justice — The Courtroom of the Future

Dec 06, 2020

By Elaine Quinn

Between September and December 2018, students of the Amsterdam Law School (UvA) and Architectural Design students of the Rietveld Academy engaged in a collaborative project that involved challenging the current structures of the criminal courtroom and developing design concepts for the ideal space for justice. Thirteen innovative, inspired and thought-provoking designs were created. After a presentation to members of the courthouse in Amsterdam, including senior judges, it was agreed that two new juvenile justice courtrooms should be created, inspired by the students’ designs. The new courtrooms are due to open in early 2021, and represent a great step forward for a more human approach to criminal law. Similar projects are now underway in other Dutch cities.

On 22 July 2020, Elaine Quinn spoke with one of the founders of the project, lawyer Wikke Monster, of Freeke & Monster criminal law practice in Amsterdam. Below is Elaine’s edited account of Wikke’s words alongside inspirational imagery and words from the students’ designs.

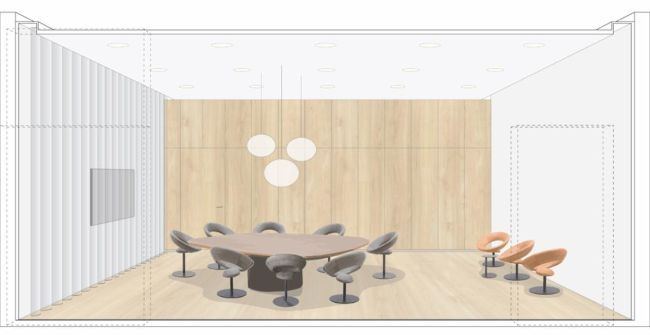

Image: New Amsterdam juvenile courtroom design

What the courthouse needs is someone who is not there to judge, but someone who hears you, who sees you… who supports and wants to help you.

— Annan Yap, Design Student

I used to practice criminal defence law in a very conventional way - always battling, always “making noise,” always working hard to defend my clients and prevent the prosecutor from winning the case.

In 2014, I founded a different type of criminal law practice with my colleague Klaartje Freeke. We transformed our way of practising law. Our focus turned to searching for the balance in a criminal proceeding. We deal with all types of criminal cases - from murder, drug trafficking, violent assault, fraud and embezzlement to more minor offences. Nowadays, the common thread is: “Are you willing to take responsibility?” I am not talking about admitting guilt here, that is a different question. I am talking about a holistic approach in which our clients work on accepting that the conflict in their lives may be trying to teach them what they most need to learn. This applies for all parties in a criminal proceeding, so also victims. We talk with our clients about the possibilities of reconciliation and forgiveness. For us, this is a much more fulfilling and soulful way to work, much closer to the true meaning of justice, and much closer to why we became lawyers in the first place.

The court-sessions are daily business for the judges. For most suspects, it is a one-off meeting with the judge who can make a life-changing decision. My ritual would contain an introduction, poetry and a mindful breathing exercise.

— Milou Francisca, Law Student

Alongside our criminal practice and day-to-day work, we have a foundation called Lawyers as Changemakers which is involved in various projects about transformation of the legal system into a more human, smarter and sustainable system. The idea for ‘A Design for Justice: The Courtroom of the Future’ came one day after I had been working at court. I was cycling back home and reflecting on the court session that day. I was trying to imagine how a suspect must feel in the environment of the courtroom having all the lawyers looming around, the judge sitting up front, the prosecutor standing to one side, and the victim possibly sitting behind. The society – and in particular judges, prosecutors and victims – so much want the suspect to be honest and take responsibility. But how can we expect this to happen in this context? Can he or she possibly feel comfortable enough to be vulnerable and to take responsibility for the offence? I found myself imagining and envisioning a different type of courtroom, a different type of environment, one which would evoke feelings of safety and trust, one which might actually encourage a suspect to take responsibility more readily.

A renovation project was about to begin on the courthouse in Amsterdam and so, with my colleagues, we took the chance of approaching the court about the possibility of engaging in a design project to rethink one of the courtrooms. They were immediately enthusiastic. At this point we had no idea that the designs would eventually be taken up and would become a reality. That has been an incredible outcome. In the beginning, we were simply allowing ourselves to envision something better.

By applying the organic and calming aspects of … nature, I’m creating an equal and soothing environment. A space that [can] engender an intimate conversation and [that can enable] personal adaptation for [the] body.

— Lisa Andren, Design Student

We planned the course as a collaboration between law and design students. From the beginning, we were certain that, for this type of new courtroom, we needed artists. I believe that we need artists to help transform the legal system. We told the students: “The sky is the limit. Do not to be held back by practical considerations.” Of course, as founders of the project, we were interested in what would really work but for the creative process itself, we did not want there to be any limitations.

Nature and the womb were sources of inspiration.

— Chaja Laurey, Law Student

During the course, which took place over 3 months from September to December 2018, the students had interactive learning sessions about the court system from judges, lawyers, a suspect and a victim. The sessions took place in the courthouse, and tours of the courthouse and the police cells were organised. It was a unique, immersive learning experience and we think there were some remarkable results. For the students, it was an extremely meaningful learning experience and this is reflected in the designs. You can sense not only the care and thoughtfulness that went into the process, but also the vision and possibility.

…I created a calming courtyard with the intention to get people’s minds out of [an] often stressful courthouse and [to] bring them back to earth.

— Annan Yap, Design Student

Apart from the design of the courtroom space itself, students looked at other important elements like the chairs, the costumes, and the various rituals and processes. One student illuminated our understanding about how our feeling of confidence, power and authority can change depending on whether we are sitting on a large, expensive chair or a small, cheaper chair. Of course, in most courtrooms, the suspects sit on small, often uncomfortable, chairs while the judges (and maybe lawyers) sit on large, comfortable, expensive chairs. Can we reflect on this and how it may be impacting behaviour in court?

The chair you are sitting on affects not only your body posture, it also affects your behaviour.

— Birte Geraerts, Law Student

Legal dress in the Netherlands is unimaginative, all of the gowns are black with a white collar regardless of the legal party’s position in the proceeding. One student worked on reimagining their look, design and colour – a really exciting prospect. Her focus was on emphasising the independence of the prosecution to support the feeling of a fairer procedure. There were thought-provoking questions around the positive and negative emotions that different colours can have, and the legitimacy of considering all of those emotions. For example, rather than ignore it, can we acknowledge fear and think about its function in the proceeding?

Just outside of the courtroom is a corridor. Leaving the courtroom without actually leaving the process is possible to stimulate conversation, thought-process and a feeling of safety.

— Esther Ruiter, Law Student

Another enlightened idea was the importance of movement, and an exploration of the courtroom as a sports field. Usually, in court, we are fairly static – wesit, we stand, we read, we talk. But if we consider the fact that there is almost always conflict and therefore tension present, we can see how important movement is. This student included adjustable spaces so that parties could move closer together, or further away, during the process; a central high table where conversations could take place; and a corridor or garden around the courtroom where he envisioned the judge and the suspect could have a private walk and talk.

Based on sawas and waterfalls, I came up with a layered arrangement for the trial participants. … Differences in height are not dictated by position or role, but by choice of the participants.

— Chaja Laurey, Student

An unexpected result of this project is the way it has been embraced by members of the courthouse here in Amsterdam. The timing was perfect because the renovation was underway and there was an openness to trying something new. The design aspect that has been taken up, and now upgraded into a professional architectural design, is the circular table.

In early 2021, two new juvenile courtrooms will open with these new designs. It feels like a wonderful success that this is moving ahead particularly with everything that is happening in the world right now. Although not all of the students’ ideas have been adopted (many because of practicalities), we want to continue to explore them. We also plan on monitoring the effectiveness of the new courtrooms when they open to see what impact the new space will have on parties and the decisions.

It feels important for us to keep moving, to keep progressing, and to keep asking questions. We are delighted that the project has also been taken up now, and will continue, in three other Dutch cities – Amelo, Arnhem and the Hague – with further collaborations between the law and art students in those cities.

We are delighted that the seed of the original vision of a courtroom of the future has been planted, and that the sprouts of something truly different and hope-giving are beginning to appear.

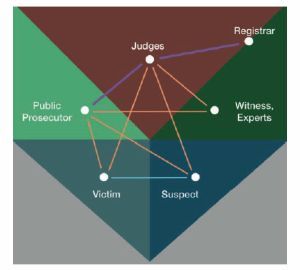

Image: Designing a Reconciliation Module, Eloi Gimeno

Image: New Amsterdam juvenile courtroom design / round table

Image: Organic and Calming, Lisa Andrén

Image: Imagining the courtroom as a sports field, Alma van de Burgwal

Image: The field of contact, Roos Brantjes

Biography

Wikke Monster (right in photo) has been a lawyer since 1999, and a mediator since 2013. Her work focuses on adults and children who have ended up in criminal cases, as suspects or victims. Wikke lets them tell their story so that they are listened to. She is committed to her clients and has a very personal approach. Together with her colleague, Klaartje Freeke (left in photo), she set up a different type of criminal law practice in Amsterdam – FREEKE & MONSTER – with a more humane and sustainable approach.

This article was reprinted with the kind permission of The Conscious Lawyer. You can also read this article on its website. And you can hear Wikke Monster speak about reimagining the courtroom on January 13, 2021 via Zoom (scroll down in the link).